The Struggle. The new kid on the sportive calendar, now in its second year. All gritty, grainy imagery, Yorkshire roses, and sexy kit. It prides itself on its savagery, its northern gnarliness, its beautiful suffering.

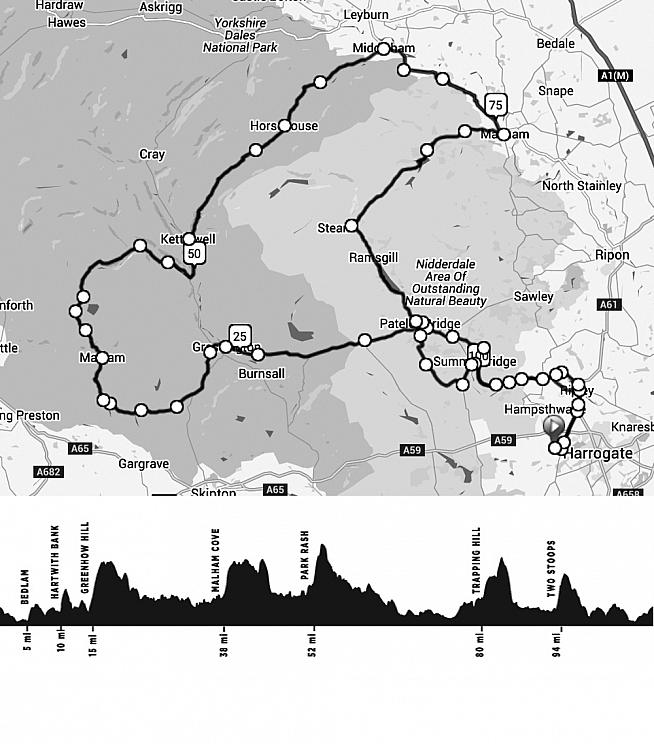

With a parcours described as being capable of 'ripping your legs off', the 175km loop takes brave and foolhardy souls around the Yorkshire Dales, over seven categorised climbs, five of which definitely fall into 'leg-breaker' territory, and three of which have made their way into Simon Warren's '100 Greatest Cycling Climbs' books.

I signed up not quite knowing what I was letting myself in for. I've ridden in the Pyrenees. I've ridden in the Alps. I've ridden in the Lake District, Wales, the Dales and Exmoor. Yorkshire can't be that bad... can it?!

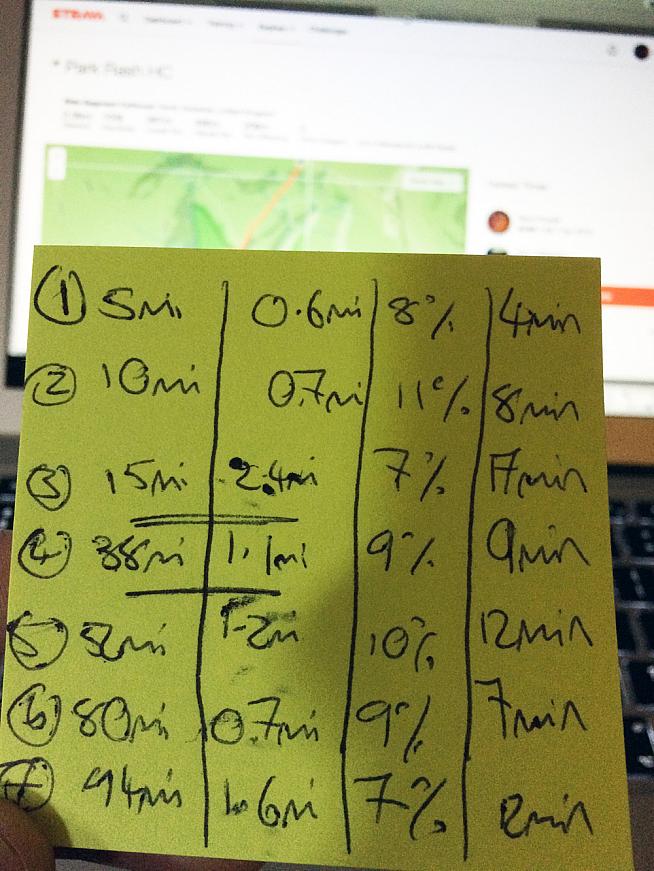

I made the mistake of casting an intrigued eye over the Strava segments of the key moments of suffering on the Friday night before the ride and broke into a cold sweat. Perusing the profiles online, looking at the sections of 25-30% gradient, I could feel my heart beating a little heavier. Having had a few months of training not quite going my way, trepidation hit, big time.

Too late now. My name's on the list, I'd recruited a foolhardy victim to join me, the Premier Inn was booked. My fate, and that of my victim-in-crime - ex-Olympic rower and smasher of Strava segments Chris Bartley - was sealed.

The prelude

An early alarm and feeling of fear startled me from a suboptimal slumber in my hotel bed on the morning of the ride. The rash choice of wine to wash down my overly-rich ragu had sent me into an initial coma, but the rest of the night was spent waking in fits and starts constantly thinking of that 4.45am buzzer.

After forcing body and brain into motion with aeropressed coffee and a stagger into the shower, feasting began. My usual Premier Inn ride breakfast was forced down with the feel of a man on death row chewing his final steak. Pots of porridge, bananas, peanut butter, bread, ham, cheese, and, in Chris's case - and this would become a theme - pork pies - were crammed into bellies not ready for such filling at that time of day. By the finish I was so full of food and trepidation I actually thought I wouldn't go into my bibs. Thankfully, the most important part of the morning, those moments of silent and solitary reflection in the bathroom, made me feel a bit more streamlined and I wedged myself into my shorts.

We got to the event HQ to find the site surprisingly quiet. With a sold-out field of 1,000 riders, The Struggle is by no means a small event but it still feels intimate compared with some of the behemoths of the sportive calendar. It's testament to the quality of its conception, marketing and organisation that this newcomer on the scene seems to punch well above its weight.

On getting out of the car and into the windswept HQ, the initial clothing plan was nearly thrown out the window, as it felt bloody cold. The wind was biting. However, having invested a lot of time in the past 48 hours poring over weather forecasts, I wasn't changing now.

Into the trenches

A relatively small field meant that after a short briefing we were on the road with no delay or fuss. Unlike some mega-sportives, there were no big fast groups powered by the willy-wavers and we soon dispersed into little clusters or lone men. Sent into the trenches of the Dales to do battle. No strength in numbers here: the Dales had the upper hand.

It all started innocently enough. The roads were rolling, the sky blue and clear, the nerves clearing.

The first categorised climb, up through the ominously named village of Bedlam, hardly even qualified as a climb. A mere nipple.

The second climb of Hartwith Bank was more of a test, and some were walking it already. I could barely believe it! The ramps up the steep (maybe 15% at points?) and claustrophobic little lane were certainly testing, but nothing to bring tears to the eye.

Greenhow Hill followed shortly after, and compared with what was to come next it has failed to imprint itself on my memories of the day: I don't really remember it to be honest. These first three climbs, on fresh legs and glycogen-loaded muscles, felt straightforward and nothing to present immediate concern. However, the Machiavellian route masters of the Struggle had still managed to wedge 700m of climbing into the first 15 miles. The first bites of the legs had been taken.

Chris's legs were clearly free of any sort of concern however. With an engine that would make Clarkson purr with pleasure and an ability to suffer honed over years of the rigours of the GB Olympic rowing programme, the man is a beast, and he looked like a caged tiger pootling along with me. But now the moment arrived to let the beast off the leash and let him romp wildly through the lanes.

We said our goodbyes, and I resolved to take the remaining 80 miles in splendid, torturous isolation. Me and the wild Yorkshire Dales. The resolute hero battling the elements in glorious solitude... However, as I watched Chris rampage down the road at an unfathomable speed, covering the kilometres with ease, my spirit drooped a little. (If, like me, you're missing Chris already you can hear an interview with him on my website: mountainmutton.wordpress.com)

By now we were in the very depths of the Dales, and it's amazing. The thing I love about bikes is the places they can take you, and I'm a particular fan of the wilder, more isolated, pre-wifi, Starbucks and avocado-on-toast environments. The Dales are a gloriously apocalyptic environment, windswept moorlands pockmarked with ragged sheep that are probably tougher than Fabian Cancellara, stone walls that felt from another age, and pure and utter quiet. I loved it.

The first feed fell on about 28 miles, and I'd decided in the bravado of the night before that this was too early to stop. However, having drained a fair bit of fluid already and thinking that getting off the bike to ease legs as much as possible was a wise manoeuvre, I pulled over at the well-stocked and slightly crowded pit stop for a 60 second bottle refill and jelly baby grab.

The first blows are landed; a right hook from Malham Cove

Feeling comforted by full bottles and stretched legs, I cracked on over the next 10km or so of rolling lanes, and progress felt good. As is inevitable on these rides, I'd been seeing the same rider all morning, a solid looking rouleur also called Chris. I latched onto him and we shared the work, making life easier for ourselves, glad of the company. We introduced ourselves and almost immediately felt like best friends.

Then he decided to tell me all about the suffering coming along up the road, the next categorised climb of Malham Cove. At this point I start to dislike him slightly. For me, ignorance is bliss.

We arrived at Malham Cove, a gloriously windswept and bleak lane dwarfed by an enormous sheet of rock - the eponymous cove. Although in the mind ignorance is bliss, the warm-up of the first three climbs earlier in the day prepared the legs for the barbarity of the cove. Seemingly impossibly steep ramps of up to 20% were mingled with brief moments of respite via short plateaus, and the legs mashed their way to the top. It wasn't pretty.

But perhaps the cruellest part of the ascent is what follows immediately after - a good 10km of rolling, grinding roads after the climb proper. My legs were screaming to rest up on a descent, and the roads laughed at their feeble impertinence as they stayed horizontal. Maintaining a good turn of pace after such a hard climb is ruddy hard, and many an oath was uttered before the sinuous descent, and much-needed rest finally came.

The panache (read: foolhardiness) of my Nibali-like descending skills meant I lost my new companion Chris on the way off the moor, with me dropping down like a stone and he taking the more cautious approach. Rather than wait, I opted to crack on to the approaching feed station in the hope that he'd catch me - I wanted the company for my head as much as my legs.

It never happened. Just me now. The glorious solo hero.

As the village at the base of the feed approached, I couldn't take my eyes off what appeared to be a cliff face overshadowing the village; a foreboding lump of rock rising threateningly over the puny dwellings below. I knew that the next climb - Park Rash - would take us up it in one way or another. My chamois remained clean, but there were more than a few rumbles of terror in my stomach.

The uppercut of Park Rash

On leaving the feed station, full of soreen, mild terror, and a sick curiosity at just what was up the road, we left the village, turned left around a blind bend and BANG: 20% gradient. Thankfully it was just a warm up of 50 metres or so, and the road was pretty wide at this point so navigating around the congestion from the feed station was simple.

A little bit of a breather followed, the gradient down to 10% or so. However, a glance up the road revealed an image forever imprinted on my mind. An S-bend covering around 300m pointing seemingly directly to the sky, with around 30 riders zig-zagging verrrry slowwwwwly up the road.

I'm lucky in that my lithe figure gets me up the steep hills faster than others. However, it also meant that I'd be working my way through the crowd, battling the other foolhardy souls as well as the seemingly vertical piece of road.

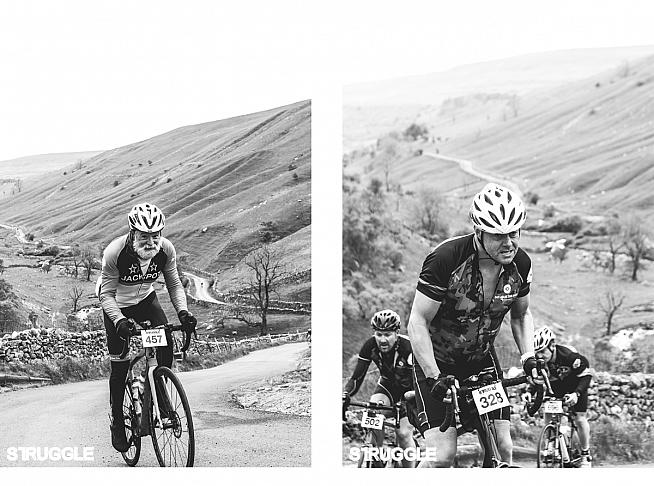

Before I knew it, I was at the bends, climbing out of the saddle, putting every ounce of strength through the bike, yanking for all my might on the bars, feeling the strain on my arms, through my core, in my hips, ass and calves. Every bit of my body shrieked in protest. My front wheel was skipping all over the shop, just like my heartbeat; I almost felt like I was going to backwards somersault off my bike.

I had to take the climb sitting down. Lowering myself into the saddle, massive torque going through the bars, I could feel the front wheel jumping and jolting again, bucking like a bronco. At the same time as my bike decided to turn into an enraged bison, attempting to buck me off in pure anger at what I was doing to it, the crowds were thick. I had no choice but to take mad evasive manoeuvres, mazing my way around like a confused rabbit in the headlights.

I shit you not, but I think my life flashed before my eyes when, as I somehow evaded one of the other whimpering riders crawling up the hill, my balance went too far over one side of the bike... I felt I was going to topple over plummet directly to the floor. Somehow, a mighty effort of neck, shoulders, arms and core kept me upright, and almost onto the mucky verge at the side of the road.

As I ground my way up the very side of the road, I was treated to an earful of an over-enthusiastic chap hollering and clanging a cowbell for billy-o, wild with sadistic excitement.

Once past the bell, the road emptied and the gradient became 'normal'; a mere 15%, and my cadence lifted to over 40rpm again. The sense of relief at staying upright, not unclipping and having to walk, and making it in some semblance of dignity, was immense. The memories of Park Rash will not leave me. Post-traumatic stress the doctor diagnosed it as.

After a brief plateau to the climb there was a second ramp, and another act of absurdity on the part of the Yorkshire road-building commission. A short but dead-straight wall of about 20%. Thankfully, it was empty when I climbed it, and after the horrors of the first section it felt relatively straightforward. The visual impact though, was something else.

After the climb of Park Rash and initial drop off so steep that you felt like you may go head-first over the bars, we were treated to a good 15-odd km of draggy 'descent'. It's in inverted commas as it was more a road that generally pointed a little bit downhill - forcing you to keep pushing the pedals - as opposed to a full-on freewheel. The narrow, twisty roads, with occasional kicks and punches, were fast, exhilarating and technical, and the only thing that made my 27kph average speed for the day not look too laughable.

However, the speedy fun was soon to end. Whilst the gradient levelled, my legs and head continued going downhill. We were about 70 miles in, I was very much on my own, and was tormented by my top tube sticker, denoted in miles, telling me there was 10 miles or so of rolling roads to go till I could get off the bike and ease up my by now very tight legs.

Cue a torturous half hour or so of looking at the distance on my Garmin, set up in kilometres, and doing the old classic 'divide by 16, multiply by 10' game to work out how far I was from the feed that my very imperial top tube sticker promised. The mind game of the turbo trainer begun; see how long you can ignore the timer or distance marker before mentally caving and checking your nigh-on immovable progress. Torture. Never hath half an hour passed so slow.

Thankfully, the mental arithmetic of my fuddled mind failed me, and the feed appeared when I thought I had at least five minutes to go (and that would have been a LOOOONG five minutes, such was my desperation).

The feed appeared before me like an oasis. It wasn't so much that I needed food, just that I needed to get off the bike and walk about for a minute or two to ease my legs. On perusing the goodies to cram into myself, the oasis of the feed zone became more than just a metaphorical watering hole in the desert, but a watering hole in the Sahara, with sun loungers, a beer fridge, and Eurosport on the telly: I spotted the pork pie plate.

Savoury food always wins, and these meaty monoliths (they were a proper northern portion, no southern fairy Waitrose mini pork pies) hit my stomach like news that your bike has emerged from an Easyjet flight unscathed.

The Dales spy him staggering and land the final blows: Trapping Hill and Two Stoops

Bladder emptied, bidons re-filled, gob crammed full of jelly babies to chew on, I slightly reluctantly got back on the bike. The legs had been stretched out a bit, but at the forefront of my mind were the two final climbs we had to negotiate: Trapping Hill and Two Stoops. There had been a lot of hype and horror on the Struggle's social media about these two almost back-to-back climbs... more warnings of 1 in 4 gradients and immense levels of suffering.

Trapping Hill hit the legs more or less immediately after the feed station, and thankfully was broken up by a plateau. I can't remember the details all that well, except that the bits either side of the plateau were, guess what? Steep as shit.

The descent certainly sticks in the mind however, a narrow and stupidly steep, stupidly fast plummet... which was kindly broken up by a group of around 10 motorcyclists who had decided to stop ALL OVER THE ROAD. It seems their pointless motorised steeds may have stalled on the way up, which is more than testament to the gradients us unmotorised cyclists had to handle.

Thankfully the descent was super straight, and a helluva lot of hollering was sufficient to warn them of my presence as I steamed through a two metre gap in the crowd behind a barrage of four-letter words.

An all-too-brief 20 minutes or so split the breakneck descent and the Struggle's final hurrah of Two Stoops. By this point I was truly toasted, and a bunch of about eight lean and lithe-looking young'uns came into view over my shoulder. Definitely time to sit in and chill I decided. Y'know, join the breakaway then attack off the front later. Yeh. Right.

After what felt like a hideous effort to jump onto the train of riders, I managed to sit in and rest for all of five minutes before a bunch of very enthusiastic lasses with cowbells, Yorkshire flags, and loud voices appeared on a bend, barking shouts of encouragement with true northern, possibly tipsy fervour.

My heart sank, because the troupe marked the start of the final climb... and BOOM, there it was, the obligatory 15% ramp to break your legs and heart right at the start of the hill. The Two Stoops was a sort of staircase of agony rather than direct wall of pain like Park Rash. This final climb teased and tortured the legs by alternating short flats with ridiculously steep bends, a few of which touched the 25-30% mark at a guess.

At this point, fighting your way over them, bent right over the bars like some sort of twisted creature from a Tolkien novel, heaving with every muscle in your body was a truly staggering effort that left neck, shoulders and arms suffering as much as legs and lungs.

The run for home was a tragic affair, far from the glorious solo break for glory I'd hoped for, tucked down onto my bike, flinging empty bidons to the gutter, solidly pumping my indefatigable legs in the final sprint. No.

The last 20 minutes were cruelly rolling over lots of short, gentle rises. I latched onto the back of a small group I caught up with and took a breath. They were going a decent pace, but when fresh I'd have gone far better on my own. I took the foolhardy decision to go around them. What followed was akin to when one lorry overtakes another on the motorway. It took what felt like five minutes to build the speed to get around the bunch of maybe four or five riders before sluggishly slotting in front of them, moving at best only 0.2kmh faster than them.

I'd intended on going around and dropping them. They easily sat in my draft. Then, to my absolute horror, they went around me. That was the true nail in the coffin. I mustered the strength to jump on and then, the fire in the belly truly dampened, having lost the will to suffer, I sat there for a good five or six km. I could probably have done that pace on my own, and sort of wanted to; I felt lazy for hitching a lift. But, by now, I just couldn't be arsed to try.

In a Dali-esque melting of time, those final 20 minutes or so felt like forever. Eager to make the Struggle stop, I eventually mustered the will and firepower to come around my group and limp solo over the cruel final lumps in the road and, if it would be possible to stagger on a bike, I did just that over the finish line.

In a nice twist on the usual goodie bag, I was immediately presented with a Struggle bidon and an OTE recovery bar. Slightly sick of sweet food, and with my appetite whetted for the combination proven to be more addictive than crack cocaine and heroin, I crept back to the car in search of a pork pie which I knew awaited me, stashed in the boot. It felt a fitting if inglorious end.

The post-fight analysis

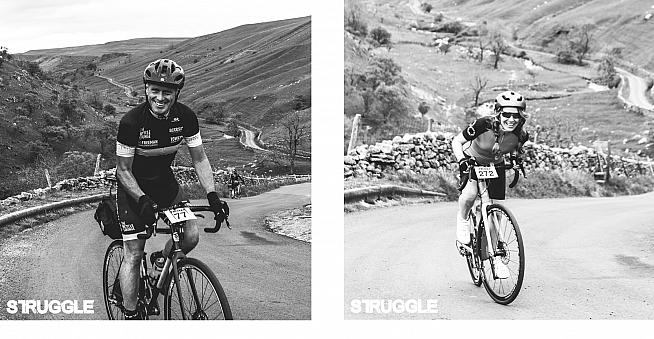

Looking back, the Struggle was a great day. The route, volunteers, HQ and admin were spot on. I make it sound like I had an awful time, but I loved every painful minute - and isn't that the point of taking on these challenges?

The final 20 miles were crippling, not because I bonked, but just because there isn't really anything that can prepare you for climbs quite that brutal if you don't have access to such severe gradients. I'd definitely go back for another go - perhaps introducing a few training rides up the brick wall outside my flat first.

Joking aside, you don't have to be an elite racer, or even naturally athletic to tackle and relish a ride like this. It was inspiring to read accounts afterwards of riders taking up to 13 hours to complete the course, and finishing with a smile on their face. Many cyclists - seasoned or new - walked the steeper climbs, and there's no shame in that. The Struggle presents a stern challenge, whatever your level of experience and fitness, and I guess that's why, even in its short existence, it inspires sellout crowds to take part.

If you fancy testing yourself on the Struggle, the good news is you don't have to wait a whole year. A sister sportive, Struggle The Moors, takes place in a few weeks in Ampleforth.

But be warned: apparently this one is even tougher...

Struggle The Moors takes place on July 9th. For more information and to enter, visit ridethestruggle.com.

0 Comments