If you're looking for a cycling challenge on a sun-kissed island with near deserted roads, the Sicily Divide could be perfect.

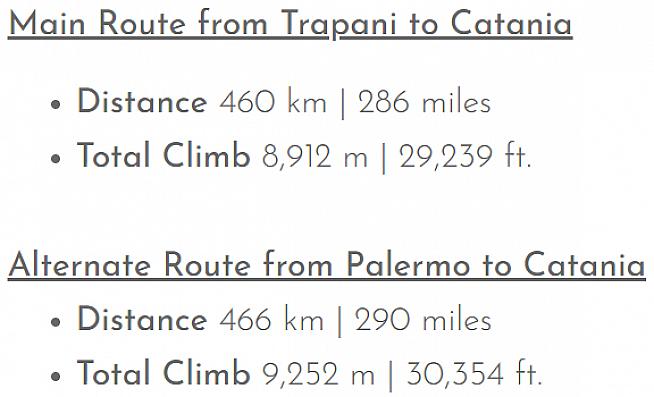

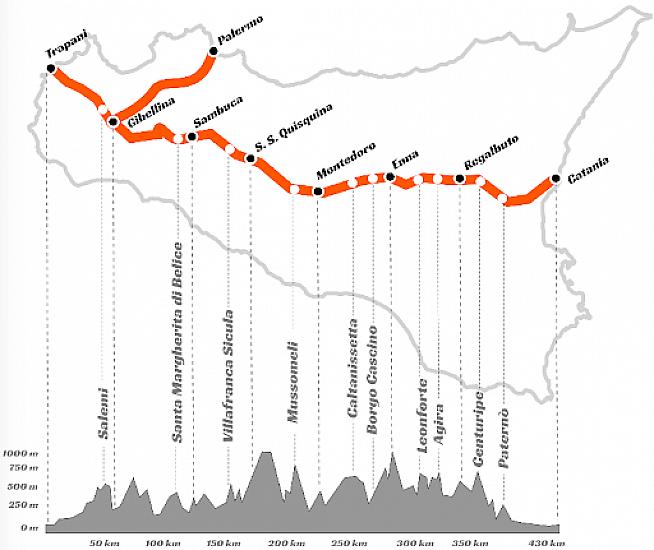

Devised by a couple of bikepackers - Giovanni and Danuta - who were bored during lockdown, this gravel route crosses the Mediterranean's largest island, Sicily. Starting either in the city of Trapani or Palermo, the route is designed to show off the island's agricultural heart, before finishing in Catania on the east coast.

The 'divide' moniker is associated with mass-start, multi-staged bikepacking races like the Tour Divide, that cater for the 'gravellatti' - semi-pro and hardcore bikepackers who have a penchant for tan-coloured bibshorts.

Thankfully for bit-part players like me, the Sicily Divide doesn't require any sleeping in bus shelters, or drinking out of puddles; it's a well researched route that can be ridden at any time of year at party pace.

Helpfully, all the planning has been done for you, and GPX files are freely available on the site. The route has been split into seven stages of about 65km each, with climbing ranging from 900 to 1600 metres each day.

Each stage starts and finishes in a town or village, with the website listing cyclist-friendly guest houses, cycle-hire companies and the locations of bike shops along the route. With budget flights to Catania and Palermo, it made an ideal February getaway for me and my wife.

Instead, we tackled the route in reverse, with a gently erupting Etna an ever-present companion for the first few days.

The ash that spews from Mt Etna has enriched the Sicilian soil for millennia, making super fertile farmland in the valleys and plains. Unfortunately, the same ash only loosely grips the region's steep hills, and deforestation has led to frequent landslips. To lessen the impact of floods and landslides, the modern trunk roads that criss-cross the valleys are elevated on concrete pillars.

At best these tracks are gorgeously dusted, compact and firm routes - making the bikes and riders purr as they seem effortless to ride. Occasionally though, we'd encounter sections they were made almost impassable. Landslips would coat these tracks in a heavy, clay soil that was often churned up by tractors and farm animals. Even with 45mm tyres and plenty of frame clearance our bikes often clogged to a standstill, forcing us to drag them through the muck, slowing progress each day.

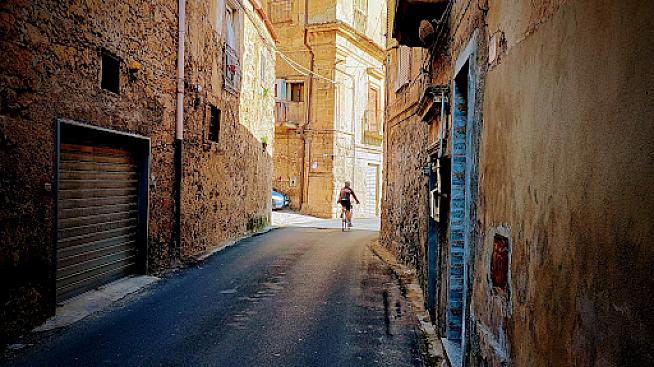

Beyond the mud, the brutally steep climbs kept our speed low. Local roads and tracks often had gradients that exceeded 20% - tough to walk, nearly impossible to ride. On the positive side of things, the reward was reaching one of the ancient hilltop towns strung along the ridges of the Sicilian interior.

Towns like Regalbuto, where we stayed on our first night and ate steak thickly coated in parmesan, or Enna, that was still towered over by Mt Etna despite being over 100km from the summit.

The apartments that towered over these lanes, shutters closed, seemed lifeless - the silence broken by the rasp of the occasional Vespa.

Pedalling into these stone-faced towns felt like entering a forgotten film set. While Sicily's coast thrives on fishing, trade, and tourism, rural poverty has hollowed out the interior. In Paterno, we found a rubble-strewn outdoor velodrome - abandoned, overgrown, and fading into a modern Roman ruin.

In the commune of Sambuca di Sicilia I found my favourite: Minni di Virgini - or 'Virgin's Breast'. This large dome-shaped cake, topped with a cherry, was filled with cream, chocolate, and green-coloured sweet pumpkin. Whilst the filling may not have been anatomically accurate, it was delicious.

In the evenings, these towns came to life a little. In Regalbuto, whilst we cleaned our bikes, the locals gathered for a festival we could hear from the guest house. Once our bikes were clean and we'd washed our kit we ventured outside to join in the fun.

The music had stopped and the PA system was being dismantled. There were a few children in costumes milling around with their families, whilst brightly coloured confetti was being swept into neat piles in the town square. This was the closest we came to evening entertainment. It's not that we had visited these towns 'out of season', it was more that these towns and the people in them were simply quietly getting on with their normal lives as we passed through them on our bikes.

The few people we did meet in these towns were welcoming, friendly, and curious about our ride. Guest house and restaurant owners knew about the Sicily Divide project and seemed to appreciate its attempt to attract visitors away from the coast. But they knew we were visiting to enjoy the journey and marvel at the beauty of the natural landscape. The towns along the way were pretty enough, but once we'd found somewhere nice to eat and a supermarket piccolo - where we'd stock up on bottled water and essentials for the next day - we were ready for bed.

The Sicilian countryside recently starred in the Netflix drama The Leopard. Praised for its 'sultry', 'lush' and 'sumptuous' visuals the hit mini-series showcased the landscape beautifully.

What sets it apart isn't just the breathtaking scenery but the blissful solitude of its near-empty roads, where you can cycle for hours without encountering another traveler. While we occasionally spotted someone tending the vineyards, olive groves, or fields, the landscape felt largely self-sustaining, with only the occasional tractor or passing shepherd hinting at human activity.

Whilst the farmers were hidden in the day, their dogs did a great job keeping guard. Some Sicily Divide riders have complained about the viciousness of these dogs that they claimed roamed free. These complaints seem misplaced to me. Sure, some dogs barked, growled and bared their teeth when we rode past their homes, but they were behind fences and just doing their doggy job. The few dogs we encountered off-leash showed little interest in us.

One helpful local we met went to great lengths using Google Translate to warn us about some fierce hounds ahead, and suggested we carry stones for defence. I followed this advice, picking three muddy rocks that were about half the size of my fist. The dogs never materialised and as I laboured up each slope that day, I cursed the extra kilos of unnecessary ballast I carried. Needless to say, we'd ditched the stones by the end of the day.

If rural Sicily has a problem that is going to put off visitors it isn't the dogs. Instead, it is the industrial levels of fly-tipping that is a real blot on the landscape. Particularly on the outskirts of Catania, we were shocked by the levels of household litter and industrial waste dumped along farm roads.

The frequency with which we'd come across these impromptu tips indicated that this was a widespread and well-established problem. These Strade Bi'manky were a common sight. We learned that this is the result of poor infrastructure - there is just one licenced landfill site on Sicily - and corruption. The disposal of rubbish in Sicily is reportedly controlled by organised criminals in cahoots with corrupt officials. So in addition to being a group of ruthless and depraved criminals, it appears the Mafia are also quite the litterbugs.

It would take far more than the anti-social behavior of slick-haired criminals in thin socks to ruin our holiday. We soon became desensitised to the litter and focused instead on the natural early-spring beauty that was erupting all around.

Thick swathes of wild flowers fighting for space amongst the cacti, butterflies flitting around roadside margins, raptors patrolling the skies above. It felt like we'd been invited to an exclusive viewing - the only audience for spring's first rehearsal.

In the final days of our trip, we rode through the heavily depopulated Belice valley, once home to over 100,000 people. Two earthquakes over two days in January 1968 killed 231, injured 1000, and left the rest of the population homeless.

Rather than rebuild the four towns that were razed in the earthquake, the Italian government decided to rebuild from scratch entirely new towns in nearby locations. Despite hiring renowned architects, this grandest of grand designs was ultimately a folly. These Nuova towns were designed to house upwards of 10,000 people, but were rejected by many of the earthquake survivors who felt like refugees in their own backyard. Some resettled elsewhere in Sicily, whilst many left for a new life abroad.

Despite striking looking apartments being available to buy for just a few thousand Euros, these towns now have fewer than a couple of thousand inhabitants, and have come to resemble the ghost towns they were designed to replace.

We spent an afternoon exploring the abandoned ruins of Montevago which have been left to stand as a memorial to the earthquake. Artists have painted murals on the crumbling buildings, and visitors have left clothing, shoes and food as tributes to those who were killed or displaced in 1968.

Sicily has a rich history of being invaded and settled by all the big players from the ancient world and the Middle Ages. As always, invading cultures eventually became assimilated and left their mark on the island, not least in the capital Palermo. Founded by the Phonecians around 734 BC, its cathedral boasts a blend of Gothic, Norman and Moorish elements.

When the Spanish ruled the city in the 16th and 17th century they built grand baroque churches and palaces that dominate the skyline. In the 19th century the Bourbons built the Teatro Masssimo - one of Europe's largest opera houses.

We gave in to the temptation to just sit down, enjoy one last arancini and soak in the city's vibrant energy. We reflected on the journey - some stunning views, a lot of hard climbs, a bit of mud - and it felt like we had earned this final stop.

While Palermo had its appeal, it was the quieter, more rugged roads of Sicily that would stay with us the longest, along with the extra pounds I'd gained, courtesy of La Dolce Vita.

For more information about riding the Sicily Divide, visit sicilydivide.it.

0 Comments